Navigating the Future: The Power of Climate Scenarios

Arun Kelshiker

20 years: Asset management and stewardship

“Climate Scenarios aren’t forecasts, but data-driven narratives that help companies think through different possible futures.” - Mark Carney*

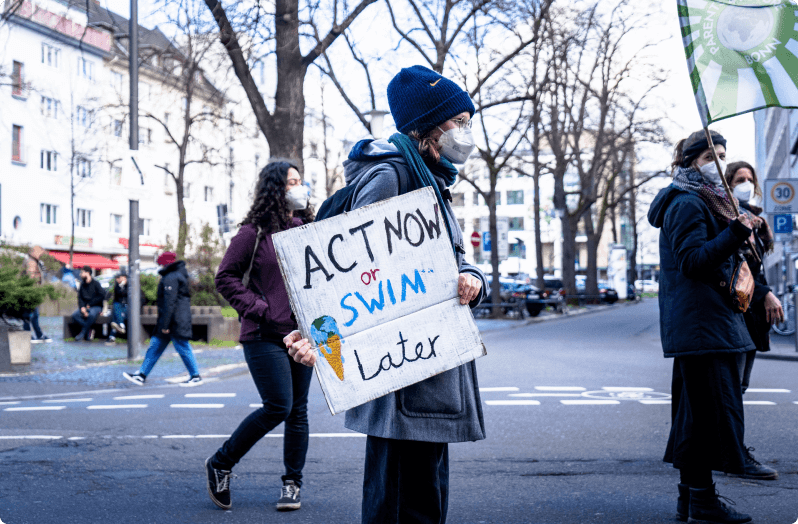

The complexities of the global climate crisis and its impacts across multiple dimensions have given rise to unprecedented global challenges. Governments, corporations, investors and affected stakeholders are having to make crucial decisions, ranging from our present and future energy mix to how we will produce goods and services with very limited information on how our future will play out. Climate scenarios are a key tool to help navigate society towards a sustainable future amid a backdrop of tremendous uncertainty.

Understanding climate scenarios

Climate scenario analysis provides an integrated approach to thinking about how the world could evolve, informing decision-makers in a structured and systematic way about possible future states and ultimately allowing them to better understand the interrelated impacts of climate change across societies, economies and the environment. Key benefits include a better understanding of the dynamics driving future outcomes, associated leverage points, increased transparency around the factors involved and a more thorough assessment of potential risks. Scenario analysis has long been used within strategic planning to add fresh and more holistic perspectives and improve resilience and climate scenarios are focused scenarios delivering relevant insights. They are recommended by the TCFD, the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures when making climate strategy disclosures.

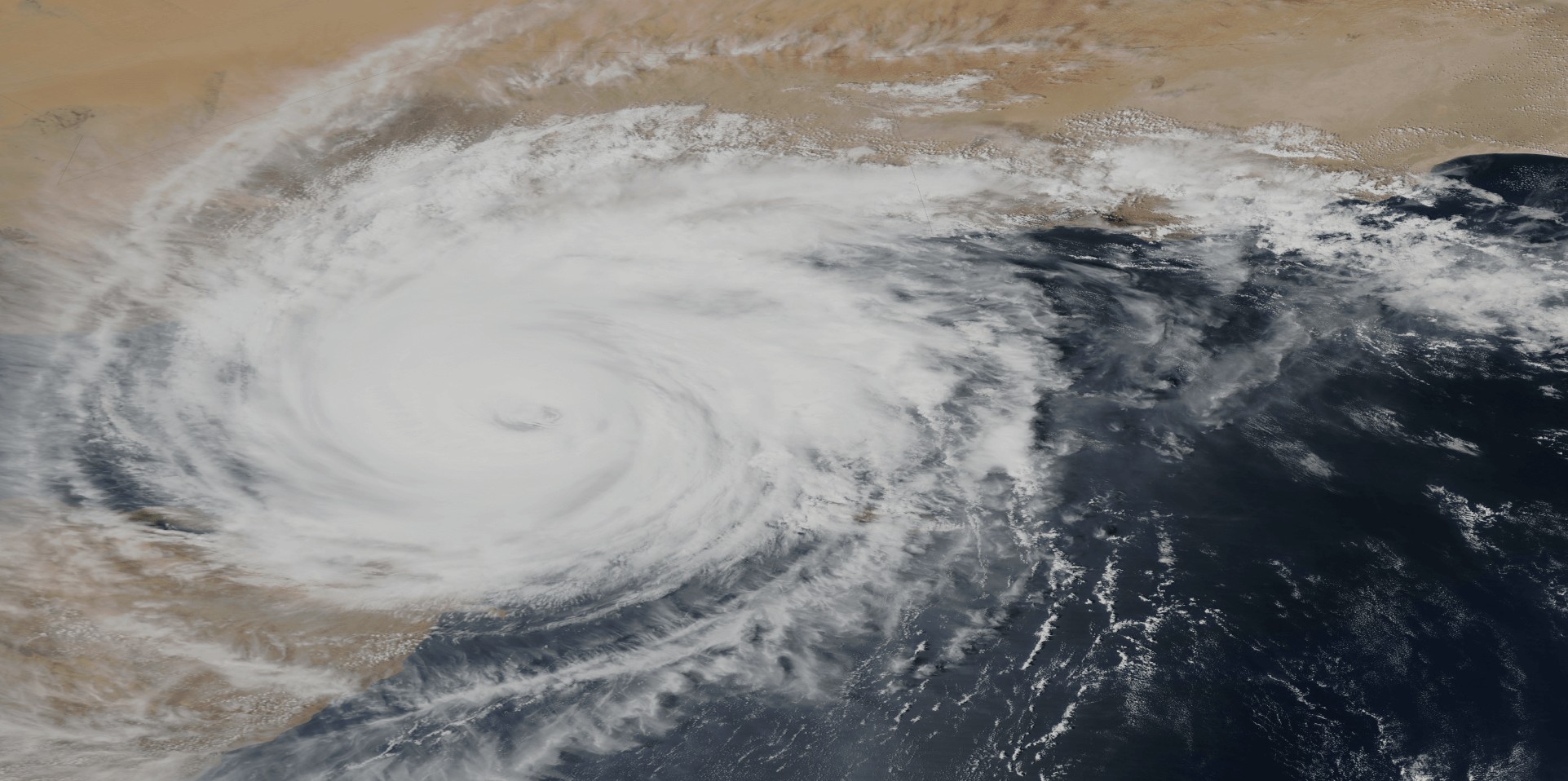

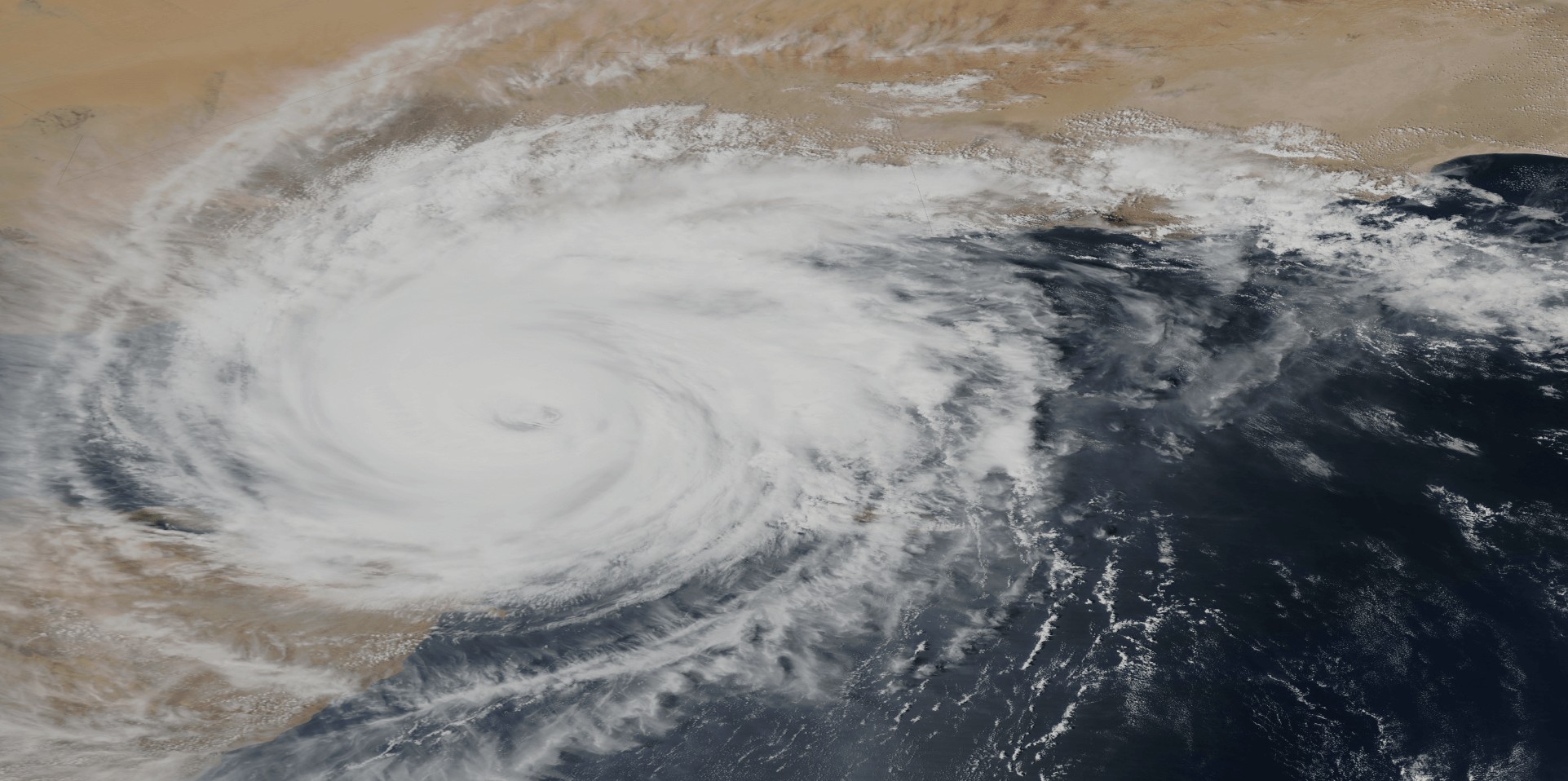

When looking at climate scenarios and climate risks, it is helpful to make the distinction between physical risks and transition risks. Physical risks stem from the impacts of exposure to climate hazards such as extreme weather events. Transition risks are associated with our journey towards a low carbon economy, such as the costs arising from stranded oil assets. Institutions will look to incorporate both physical and transitions into their scenarios.

With transition risks, institutions will assess whether their strategies and portfolios of activities align with the implications of globally projected GHG emissions trajectories, for example the impacts of a carbon tax.

It is useful to differentiate between normative and exploratory climate scenarios. Normative scenarios take a future outcome as a starting point, for example net zero targets, and are constructed by working backwards. By contrast, exploratory scenarios, recommended by TCFD, establish different sets of starting conditions and see how they evolve.

Climate scenario analyses can vary depending on an institution’s unique goals: for example, climate scenario analysis for a company making decisions about its future operating model may contrast with the aim of a bank performing climate scenario analysis and climate stress-testing to model climate impacts on its lending portfolio, or of a regulator assessing in aggregate the relative stability of a financial system under climate scenarios.

Climate scenarios have a series of critical parameters and assumptions that act as key drivers and help define development pathways over the scenarios’ time-horizon. These are generally grouped into major categories including:

- the parameters used e.g. discount rate, carbon price, energy demand and mix, macro-economic and demographic variables, technology, policy and the price of key commodities and products etc.

- analytical choices made for the scenario analysis e.g. quantitative vs qualitative or directional inputs being used, time horizons, breadth and scope of the analysis, climate models and data sets used etc. and

- business impacts/effects on an institution’s earnings, costs, revenues, assets, capital allocation/investments etc. Integrated assessment models (IAMs), which analyse the interaction of societal and economic choices and their impact on the planet, are extensively used by stakeholders including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). IAMs draw extensively on economic models and can address both general and specific questions.

Key climate reference scenarios

While customised climate scenarios are valuable inputs for institutions facing different sets of challenges, often as a starting point; standardised reference scenarios provide a strong basis for climate scenario analysis. Reference scenarios provide a set of pre-agreed estimates and trajectories around key factors including global greenhouse gas emissions and are supported by socio-economic narratives and assessments around climate impacts. The most popular and widely-used reference scenarios include the IPCC, the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening of the Financial System (NGFS).

IPPC: Future GHG emissions and the factors affecting them

IPCC current scenarios are essentially driven from the perspectives of how future atmospheric GHG concentrations will change – representative concentration pathways (RCPs) – as well as how changes in factors including population, economic growth, education, urbanisation and technology will affect future GHG emissions – shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs). The IPCC, in its most recent sixth assessment report, said that “Global GHG emissions in 2030 implied by nationally determined contributions (NDCs) announced by October 2021 make it likely that warming will exceed 1.5°C during the 21st century and make it harder to limit warming below 2°C.” NDCs are the self-defined national climate pledges under the Paris Agreement.

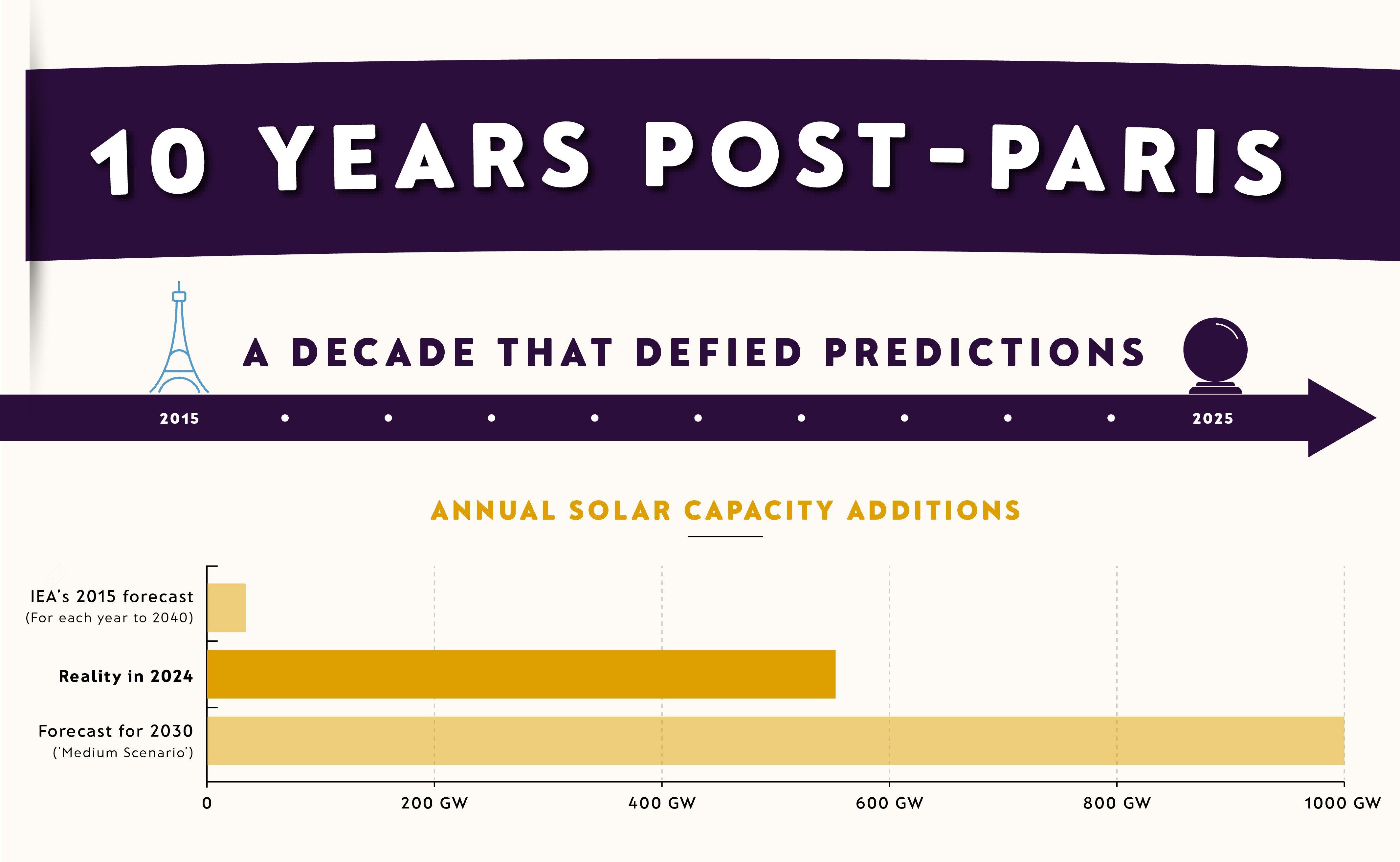

IEA: The Energy outlook, in three different ways

In its World Energy Outlook 2022, the IEA came up with three main scenarios:

- A Net Zero Emissions by 2050 (NZE) Scenario: a pathway to the stabilisation of global average temperatures at 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels,

- An Announced Pledges Scenario (APS): this scenario assumes all governments will meet in full and on time, all of the climate-related commitments they have announced … and

- A Stated Policies Scenario (STEPS): this scenario is based on a detailed sector‐by‐sector review of the policies and measures that are actually in place or under development i.e. it looks at what governments are actually doing to reach the targets and objectives that they have set, highlighting that rising energy demand driven by economic and demographic forces takes place in every scenario.

With these scenarios, it is also worth highlighting the difference in APS and STEPS or the implementation gap based on what countries have pledged to do and what they are actually doing, as well as the ambition gap, the difference between APS and NZE as it reflects that pledges collectively made are not ambitious enough to limit the global average temperature rise to 1.5°C.

NGFS: The future, from every angle

NGFS scenarios, while critically supporting central banks, supervisors and financial market participants, also provide comprehensive decision-useful financial and economic analysis and inputs into climate scenarios for related stakeholders in an open-source platform. The NGFS provides a standardised set of transition risk, physical risk and macroeconomic variables together with the major assumptions they are based upon, which draw on existing IPCC-assessed climate mitigation and adaptation pathways. The design of NGFS’s climate scenarios looks to incorporate: atmospheric concentration of GHGs, socioeconomic context, technological evolution, climate policies, consumer preferences, and climate impacts.

NGFS’s six long-term scenarios are categorised as follows:

- The Orderly scenario assumes climate policies are introduced early and become gradually more stringent. Both physical and transition risks are relatively subdued. The two scenarios are i) Net Zero 2050 (1.5°C) and ii) below 2°C.

- The Disorderly scenario explores higher transition risk due to policies being delayed or divergent across countries and sectors. Carbon prices are typically higher for a given temperature outcome. The two scenarios are: i) Divergent Net Zero (1.5°C) and ii) Delayed 2°C.

- The Hot house scenario assumes that some climate policies are implemented in some countries but global efforts are insufficient to halt significant global warming. Critical temperature thresholds are exceeded, leading to severe physical risks and irreversible impacts including sea-level rise. The two scenarios are: i) NDCs and ii) Current Policies.

- The Too little, Too late scenario assumes that a late transition fails to limit physical risks. While no scenarios have been designed for this outcome, the NGFS suggests that higher physical risk outcomes for disorderly scenarios would apply.

The NGFS has also published five short-term climate scenarios, covering a time horizon of three to five years with the aim of overcoming limitations in macroeconomic and financial risk analysis stemming from long-term climate-economy relationships captured in its long-term climate scenarios. These short-term climate scenarios are grouped as follows:

Transition Risk:

- The Highway to Paris scenario reflects an immediate and technology-driven transition.

- The Green bubble scenario employs generous fiscal policy incentives in the form of subsidies, which lead to glut of green private investment and expenditure.

- The Sudden wake-up call scenario describes an abrupt and unanticipated transition.

Transition and physical risk:

- The Diverging realities scenario maps out possible futures with severe divergences across countries and the extent to which economies transition to net zero. This scenario is considered “Too little too late” and reflects the risk of a lack of external financing from advanced economies to developing economies and low-income countries, effectively limiting the ability to transition globally in a timely fashion.

Physical risk:

- Low policy ambition and disaster is a “Hot House World” scenario where extreme physical risk impacts are analysed.

Given the complex nature of climate scenario analysis, varying assertions continue to be made on potential outcomes including the Inevitable Policy Forecast and Forecast Policy Scenario Analysis 2023 update, commissioned by the Principles for Responsible Investment, which has a high conviction forecast of temperatures peaking at 1.7-1.8°C by the 2040s, signalling that the Paris Agreement “well below 2°C goal” will be met.

Critical debate around the robustness of climate scenarios

It is important to be aware that fundamental questions are being asked about the robustness of climate scenario modelling. Assertions are being made that, with the approach of tipping points – natural thresholds which once crossed, trigger irreversible changes such as loss of the West Antarctic ice sheet – could cascade into future new states, which have not been captured in current climate scenario analyses.

Research has showcased a major divide between economically-driven climate scenarios and climate scientists’ expectations of future states. Economists have claimed in refereed economist papers, that 6°C of global warming will reduce global GDP by less than 10% as compared to without climate change impacts.

This is in stark contrast to climate scientists, who have claimed in refereed science papers, that 5°C of global warming imply damage that is “beyond catastrophic, including existential threats” while even 1 °C of warming, which has already been passed, could trigger dangerous climate tipping points. (Institute and Faculty of Actuaries – The Emperor’s New Climate Scenarios (2023) & Carbon Tracker - Loading the DICE against pension funds (2023).

With the increasingly alarming impacts of climate change comes the need to empower leaders to take proactive steps towards more sustainable and resilient outcomes. Climate scenarios can provide decision-makers with valuable perspectives and crucial insights, supporting stakeholders in best navigating uncertain future states to ultimately achieve the goal of a sustainable world for generations to come.

*A New Horizon, speech given by Mark Carney, Governor Bank of England 21 March, 2019

Arun Kelshiker

Share "Navigating the Future: The Power of Climate Scenarios" on

Latest Insights

Concentrated power, systemic fragility: The real lesson of the Greensill collapse

11th March 2026 • xUnlocked