The electrical zero: A global warning for the energy transition

Maria Coronado Robles

The April 28 blackout, what happened and what it tells us

The April 28 blackout: What happened and what it tells us

On April 28 2025, Spain’s power grid collapsed. In seconds, 15 gigawatts vanished, roughly 60% of national demand. The blackout was immediate and massive, leaving millions across Spain, Portugal, and southern France in darkness. Transport, businesses, and essential services were fully interrupted, and it took several hours to get the lights back on.

Blaming renewables is lazy and wrong. Yes, Spain was running mostly on renewables that day. But what caused the outage was forcing them to run on infrastructure designed for fossil fuels. One that is unfit for the variability and decentralisation that renewables bring. And Spain is not alone, across the world, the energy transition is riding on outdated systems that can’t keep up. Until we fix this, more blackouts are coming.

The deeper problem behind the blackout

Spain is now “renewable rich” but far from being “renewable ready”; that’s a technical reality. Despite having one of the biggest shares of renewables in the world, when the grid began to fail, only 12% of that capacity could help stabilise it. The blackout was a direct result of a system unprepared for the energy transition it claims to lead.

Was this preventable? Absolutely. The technologies to avoid or mitigate it already exist. Grid-forming inverters, advanced battery storage and digital control systems are produced by industrial giants like Siemens, ABB, and Huawei. They’re commercial, proven, and used in countries like the UK, Germany, and Australia.

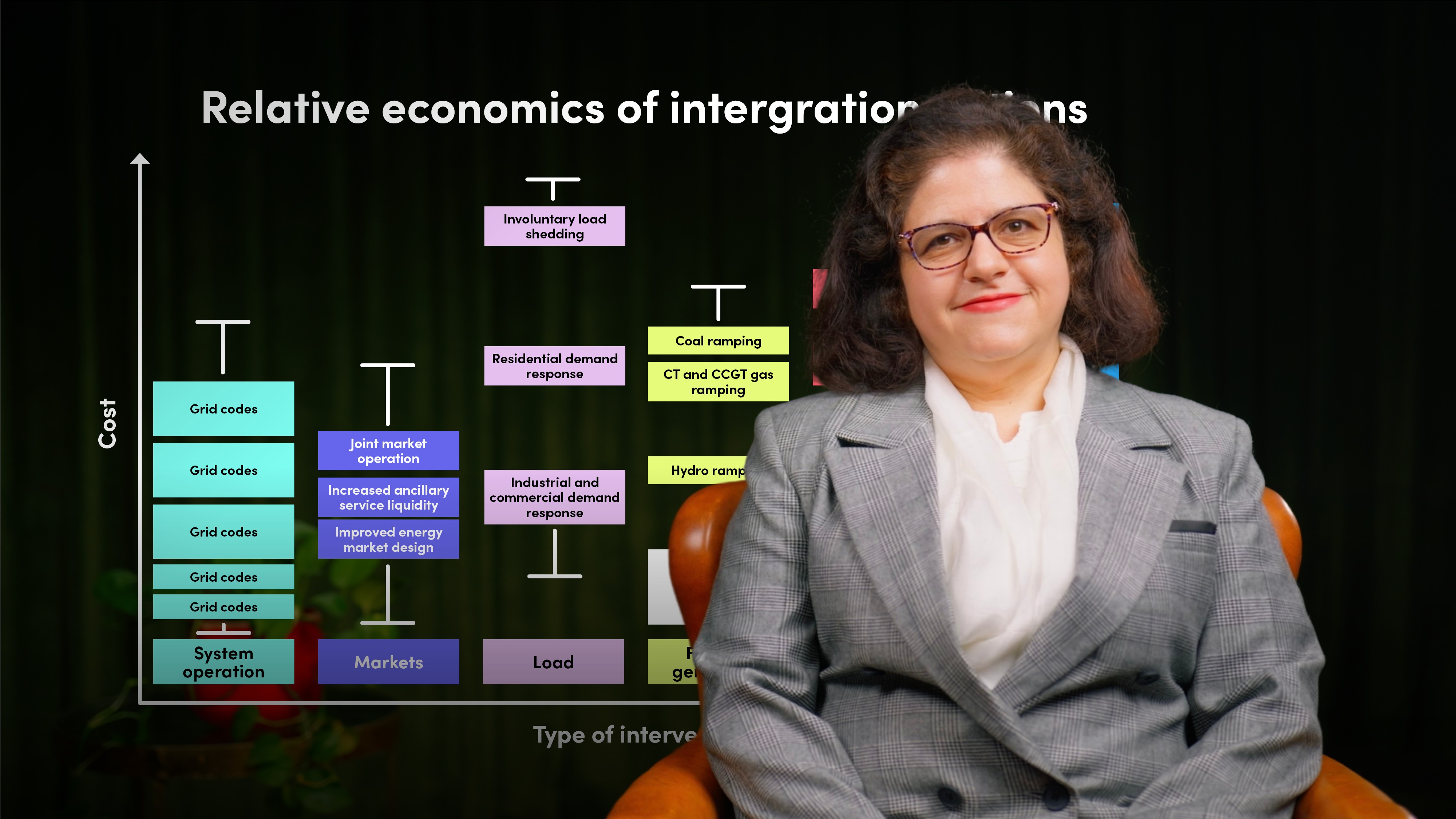

So why didn’t they prevent Spain’s collapse? Because they’re still undervalued and underused. We have proven technology sitting on the shelf. Markets reward capacity (power produced), not resilience (how well the grid can handle disruptions), and that’s become a serious liability.

Take inverters, for instance, Spain still mostly uses grid-following inverters that dump a lot of power onto the grid without stabilising it. Good enough when fossil fuels ran the show, but with renewables, stability isn’t a given. What’s needed now are grid-forming inverters that stabilise the grid in real time. They exist and work, but are not required, barely incentivised, and rarely installed. Are they expensive? Upfront, yes, but not compared to the €1.6 billion cost of a single blackout, equivalent to 0.1% of the country’s GDP.

Storage is another blind spot. Spain has 10 GW of storage, but 99% of that is pumped hydro. Modern batteries like lithium-ion systems only account for 60 megawatts. Why so little? Again, not a technology problem, it’s regulation. Permitting is slow, and projects aren’t required to include storage. There’s no mandate, no reward, so the market doesn’t move.

Regulation & investment, the missing muscle

This wasn’t a surprise; Spain’s government had been formally warned months earlier by its own grid operator, Red Eléctrica de España (REE), about the risk of electrical failures without urgent upgrades. The April blackout proved them right. Could the government have fixed this in just a few months? Probably not, but this has been on the radar for a lot longer.

Since then, we’ve heard plenty of promises, sixty governments, a hundred companies, billions on the table. But promises don’t keep the grid running, capital does.

But money doesn’t move on good intentions alone. Private capital is ready, investors like BlackRock and Macquarie, and pension funds have billions available for investment, but they won’t fully commit at the scale needed until deals are derisked. That means regulatory reform, streamlined permitting, and clear revenue models. The European Investment Bank has said it plainly, the grid won’t be investable until the rules change.

To avoid more crises, Spain needs to move fast. That means clear mandates for grid-forming inverters and battery storage in every new project, not just more wind and solar. The focus must shift from flashy generation targets to the unglamorous backbone of critical infrastructure. No more feeding renewables onto a grid that can’t support them.

Investment strategies have to evolve too. The International Energy Agency (IEA) puts the cost of upgrading Europe’s grid and storage at over $1 trillion by 2030. That’s a massive investment, and public money won’t be enough. Private capital and public-private partnerships will have to carry part of the load. But investors won’t write those checks without regulatory certainty, bankable projects, and long-term returns.

Utilities are moving, too. Iberdrola, Enel, and EDF have all announced record grid investment plans. Iberdrola alone is committing €12 billion this year, part of a €150 billion plan through 2030. Most of it is to modernise and digitalise the grid. But even the biggest players admit that without faster permitting and stable regulation, their timelines will slip behind what’s needed.

With the right regulatory, financial, and administrative conditions, Spain could accelerate the deployment of advanced inverters, energy storage systems, and digital control technologies, particularly in regions with high renewable energy reliance. In the best-case scenario, Spain would still take at least five years for the first significant wave of deployment, with full national impact likely taking 10 to 15 years, if not more.

However, the speed at which this progress happens will depend on how quickly the government can push through the necessary reforms. Will it move fast enough? Hard to say. Political debates are slow, and the government faces opposition from various sides. Left-wing parties, including the ruling Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), advocate for strong state intervention and regulatory mandates, while the right-wing Popular Party (PP) favours market-driven solutions, and Vox, known for its nationalist and far-right conservative views, opposes most climate policies altogether. This political mix creates the perfect environment for nothing to get done. Not quickly, anyway.

Here is the hard truth: We’re failing ourselves. We have the money, the technology, and the expertise to build a modern, resilient grid. What we don’t have is the policy muscle to match the pace of change. Until governments stop managing yesterday’s grid and start building tomorrow’s, we’ll keep mistaking activity for progress, and we’ll keep the lights on by luck, not by design.

Maria Coronado Robles

Share "The electrical zero: A global warning for the energy transition" on

Latest Insights

Natural capital: The strategic risk still missing from business planning

14th August 2025 • Maria Coronado Robles

From mandate to momentum: Regulation as a force for positive change

1st August 2025 • Maria Coronado Robles

Understanding the UK PRA's newest climate risk management expectations

25th July 2025 • David Carlin

Are knowledge gaps or disparities blocking your sustainability success?

26th June 2025 • Maria Coronado Robles