Climate action at a crossroads

David Carlin

Head of Climate Risk

Understanding COP29's key outcomes and missed opportunities

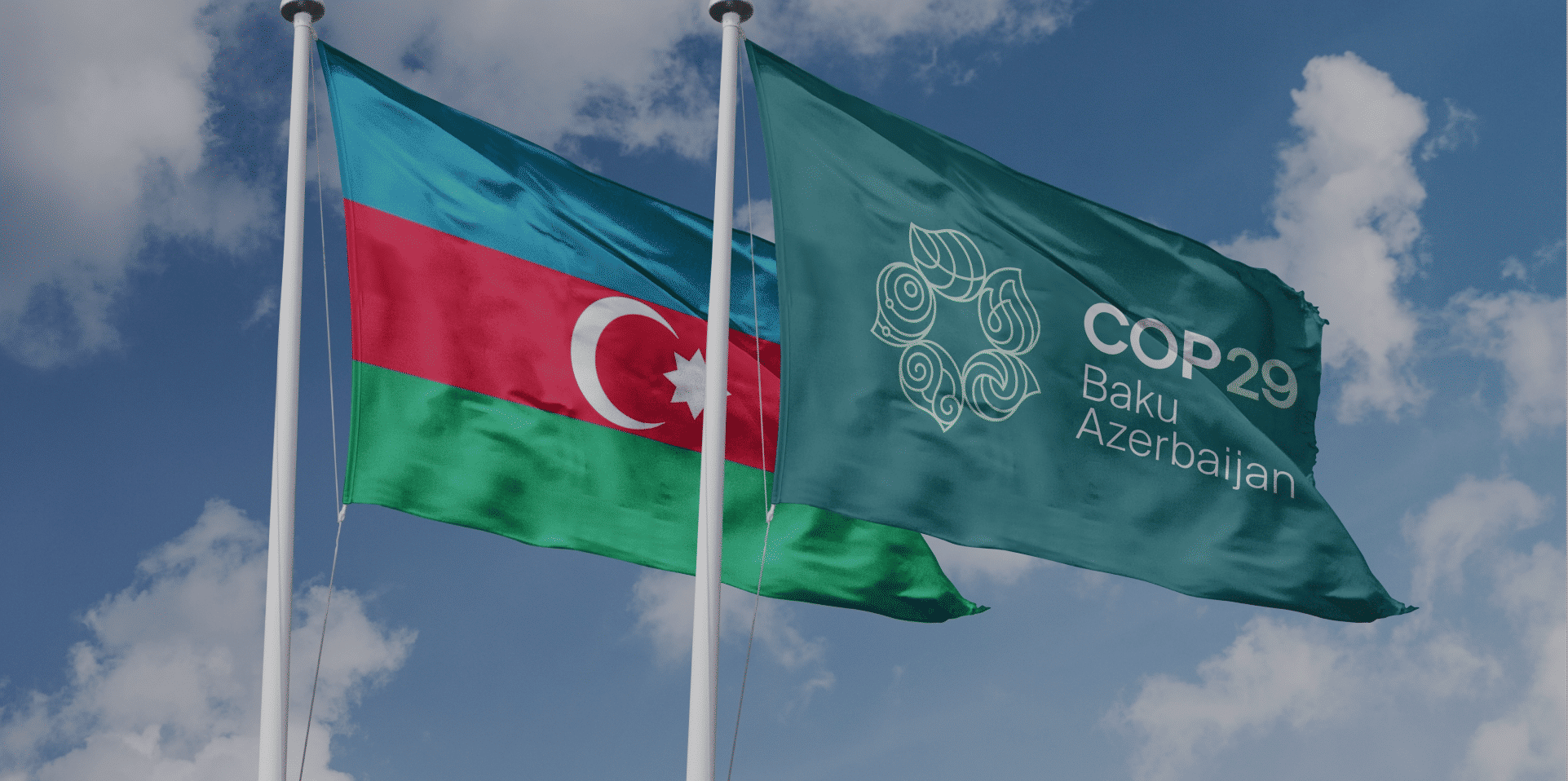

With global temperatures nearing 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels this year, COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, arrived at a pivotal moment in our fight against climate change. Delegates from nearly 200 nations gathered to make progress on scaling climate finance, reducing fossil fuel usage, and operationalising key aspects of the Paris Climate Agreement.

After a marathon set of negotiations over two weeks, the final text reflects some incremental progress in climate finance commitments, carbon market structures, and transparency. However, as the world races towards dangerous levels of warming, incrementalism is no longer enough. From the modest increase in funding for developing nations to the inability to progress on phasing out fossil fuels, Baku fell short of the transformative agreement hoped for by many climate campaigners. The article dives into the final texts and provides a primer on what was agreed, what remained unresolved, and where the world goes from here, with a critical COP30 looming in 2025.

Climate finance: A $300 billion “core” commitment

As expected, climate finance was a central theme at COP29, which many billed as the "Finance COP." Parties arrived in Baku with the aim of agreeing to a New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on climate finance. The prior goal was set over a decade ago and promised $100 billion in climate finance from developed nations to developing ones. However, it took years for this number to be reached, and when it was, much of the finance took the form of market-rate mechanisms that increased indebtedness in developing nations.

In the final hours of COP29 debates raged over what the new commitment would be from developed nations. At one point, many developing nations walked out in protest. For a time, it seemed that a deal might not be reached at all. Yet, by the end of COP29, the delegates salvaged a deal to increase climate finance from developed nations to $300 billion annually by 2035. This marks a fraction of the trillions needed by developing nations to meet their climate mitigation and adaptation needs, but it is a step forward.

While the final text also referenced a broader ambition to mobilise $1.3 trillion annually from all sources by 2035, including private finance, the mechanisms for achieving this remain vague. The recognition of private finance as critical to scaling up climate action is promising, but without clearer strategies for mobilisation, the gap between pledges and implementation will persist.

Fossil fuels: A conspicuous absence

The summit began on an ominous note, with the Azerbaijani host referring to fossil fuels as "gifts from God.” These remarks foreshadowed the difficulties in progressing on a fossil fuel phase out during the second consecutive COP in a major fossil fuel-producing state.

While stronger language around the transition from fossil fuels made its way into draft texts, the final text was little changed from that agreed upon at COP28 in Dubai. That text referred to the “phase-down of unabated coal power” and “phasing-down inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.” Activists and vulnerable nations were understandably livid at the failure to garner stronger commitments on the reduction of fossil fuel use, noting that, after 29 COPs, fossil fuels are barely referenced despite being the primary driver of global emissions.

This failure to address fossil fuels underscores the disconnect between the urgency of the climate crisis and the incremental nature of international negotiations such as the COP process.

Adaptation and loss and damage: Progress and gaps

At COP29, adaptation was a contentious yet central area of discussion. The conference put significant focus on operationalising the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), established to guide countries in protecting people and ecosystems from the impacts of climate change. COP28 in Dubai had launched the UAE-Belém framework, a two-year work program featuring thematic targets from water security to preserving cultural heritage. The framework also included a mandate to develop indicators for measuring adaptation progress.

COP29 represented the halfway point of this program, but negotiations underscored the deep divisions among parties. A critical sticking point was the inclusion of indicators for “means of implementation” (MOI), widely interpreted as referring to adaptation finance expectations. Developed nations challenged the MOI language and in the final text it was softened to include “enabling factors for the implementation of adaptation.”

Progress was also made on operationalising the Loss and Damage Fund, with initial disbursements expected by mid-2025. The fund was established at COP28 to provide climate disaster relief for vulnerable nations. However, the agreed New Collective Quantitative Goal (NCQG) does not include money for the Loss and Damage Fund, leaving developing nations questioning how sufficient resources will be secured. In the words of UN Secretary Antonio Guterres, current loss and damage commitments do not “come close to righting the wrong inflicted on the vulnerable.”

While these outcomes reflect progress, they also highlight the need for greater ambition. Adaptation finance and support for loss and damage must be scaled up to address the growing challenges faced by the most vulnerable nations.

Carbon markets: A boost for credibility

Carbon markets, governed under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, were a bright spot at COP29. Delegates finalised guidance for Article 6.2, which covers country-to-country emissions trading approaches, referred to as internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs). The final text clarifies the use of ITMOs and prevents double-counting of emissions reductions.

Delegates also reached a consensus on implementing Article 6.4, which governs international carbon markets. The EU referred to the agreement as the “rulebook on carbon markets,” and it should go a long way toward rebuilding trust in carbon markets, which have been rocked by credibility issues in recent years. COP29 created a UN-backed framework for carbon markets and credits to follow that is aligned with “the best available science.”

These agreements are expected to drive more funding into carbon markets, supporting conservation efforts, nature-based solutions, and carbon storage initiatives. However, experts caution that robust enforcement mechanisms will be essential to maintain the integrity of these markets.

Wins: Transparency and accountability

COP29 marked another win for transparency, with enhanced reporting requirements for emissions, climate finance, and adaptation progress. Several nations submitted their first Biennial Transparency Reports (BTRs), offering detailed insights into their emissions trajectories and efforts to meet their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which are country-specific commitments under the Paris Agreement for emissions reductions.

This focus on transparency aligns with pre-summit calls from public, private, and civil society actors for more robust reporting frameworks. These measures are critical to ensuring progress on climate goals and ensuring that market and governmental actors have the information they need to make informed decisions about climate finance.

Looking ahead: COP30 in Belém

As the stage shifts to COP30 in Belém, Brazil, the coming year will be critical for translating commitments made at COP29 into action. At the national level, the central focus of COP30 will be the submission of updated NDCs. While a few countries have already submitted their targets, most nations will do so in the months ahead.

Some hopeful signs have come from host nation Brazil, which committed to a 66% reduction in emissions by 2035 from 2005 levels, and the UK, which has pledged an 81% reduction by 2035 from 1990 levels. These targets are promising, but their success will depend on clear sectoral strategies and financing mechanisms to support implementation.

COP30 offers a critical opportunity to bridge the gap between ambition and action, particularly as the $300 billion NCQG begins to take shape. Ensuring these financial commitments translate into tangible progress on adaptation, mitigation, and loss and damage will be key to meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Path forward: From incrementalism to transformative change

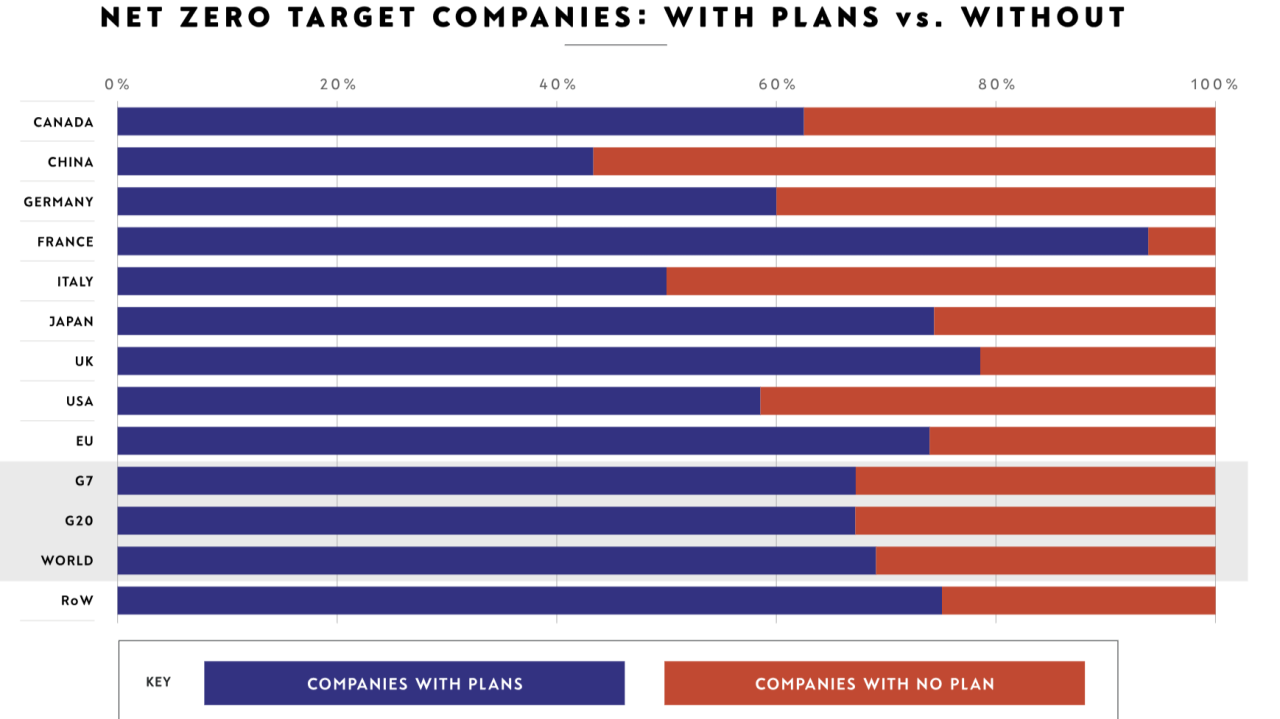

COP29 saw progress on increasing climate finance commitments, operationalising adaptation frameworks, and strengthening carbon markets and transparency. Yet, the summit also highlighted the enduring challenges of confronting climate change in a polarised world. The election of Donald Trump in the United States will be a blow to international collaboration on climate in the years to come, as he has pledged to once again withdraw America, the world’s largest economy and second largest emitter, from the Paris Agreement.

The climate crisis demands systemic change, and the COP process appears incapable of delivering it. Limitations include the need for unanimous agreements, outdated developed and developing country classifications, and an overly broad agenda. Until these issues are addressed, climate change will continue to outpace climate progress. Leaders such as former UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon and former UN climate chief Christiana Figuerres have joined the chorus calling for COP reform.

Hopefully the updated national climate pledges (NDCs) released in the months ahead will spur more transformative change ahead of COP30. However, without concerted action, the window on 1.5°C is likely to close for good.

This Insight was originally published on Forbes.com.

David Carlin

Share "Climate action at a crossroads" on

Latest Insights

Lights in the fog: Positive signals for sustainability investment

2nd October 2025 • Henry White